At the most recent Board of Supervisors meeting, the vote on the 2030 Crappy Crony Plan was postponed yet again, and board members acknowledged the need to “revisit” the TDR ordinance. This, of course, means that the same cronies who came up with the ordinance are being instructed to revise it so as to make it more palatable to the general public. The Board of Supervisors and the Planning Commission genuinely believe in the TDR ordinance as a good program.

At the risk of beating a dead horse, I’m writing about that blasted TDR Ordinance and Program again. But this time I’m letting Eric Lawrence, Frederick County’s Planning Director, do most of the talking.

On July 23, 2010 at the Charlottesville Omni Hotel, Eric Lawrence gave a presentation for the PlanVIRGINIA CPEAV’s Planning and Zoning Law Seminar on Transfer of Development Rights. You can watch a video of the presentation here. The Orange County, VA government makes the program agenda available here.

I have done my best to provide a transcript of his presentation and have posted at least the first eighteen minutes (interspersed with my commentary, of course):

I’ll tell you how we developed the ordinance–what it took to get where we are today, but aside from conversations, we haven’t actually had a transfer yet. So I just want to lay that out there.

Part of the process to get to where we are–to get an ordinance–we had to meet with a lot of representatives from our community, whether it be the farmers, the developers. And through those discussions, we found a lot of things–I guess it was an education process. And I am just going to go through a couple slides right now that sort of set the mindset as to how we got to where we are.

What we found is a lot of times a farmer has good productive land, and he is living off that land. He is creating a product; his family thrives off it. He wants to continue to farm, but the argument we’ve heard often is that “I’ve got to sell land, portion of the land or all the land, because I’ve got expenses that I’ve got to cover.

So we said, “Okay, well that’s a problem. Let’s figure out how we can work through that.”

This is incredible. People have to sell things all the time to cover life’s expenses. Sometimes that means selling their electronics, their vehicles, and even their homes. Why is it that the Frederick County government is giving special privileges to some citizens rather than others simply because they are part of a certain industry?

The big thing that we hear all the time is “My farm is my retirement. Don’t devalue it. Don’t downzone it. Leave it alone. I’ve made decisions based on that.” So we take that into consideration as we are going through the program.

The issue is, obviously–and this is an obvious one–but we always point it out to farmers: “If you sell the land to get value to pay your bills, then you can’t be a farmer anymore. Then you’ve sold the opportunity that the farm provides to you. So what can you do to help preserve that land?”

Then we said, “Okay, let’s talk to the developers.” Now, I may be saying things that are obvious, but when we started talking to people, it wasn’t all coming together, so I think it’s important to point out. And obviously a developer’s intent is to create some value out of the land, develop it into something. A lot of times he wants to increase the residential opportunities because there’s the value that he is striving for. And he recognizes the time is valuable. If he feels that today there’s an opportunity to sell land, subdivision or whatever the case is, he doesn’t want to wait what typically is about a two-year process in Frederick County to get through a rezoning exercise and get to the point where you’ve got a blessing from the Board of Supervisors. So time is money. You know, he doesn’t want to go through that lengthy process.

Why not shorten the rezoning process? How about repeal the zoning laws altogether? (Yeah, yeah, too radical…)

And the second bullet up there–the business plan–I think that’s extremely important, and that’s why we think the program we have is going to work properly. In the state of Virginia we don’t do impact fees

Thank God.

but we except proffers. So, not only, if the developer has to go through the rezoning process, you’ve got a time lapse but you also have an expectation to get that rezoning approved, he’s got to mitigate things. He’s got to address transportation, he’s got to address your capital facilities and impacts on your schools and things of that nature. So there’s an intrinsic value that he’ll have to contribute at the end of the rezoning process just through a normal rezoning.

And then we have the County’s perspective. In Frederick County we’ve had a UDA since late ’80s, and we’ve been very proud of our UDA. And what it does is it captures most of our residential development–I’ll say the majority of our residential development. We see about 30% of the residential units are constructed in the Rural Areas of the County. We want to try to reduce that percentage. And obviously the development in the Rural Areas of the County are a by-right. There’s no opportunities to recover any of the impacts on transportation, any of the impacts on your school system, your capital facilities. Those are impacts that are normally mitigated through a rezoning process, but we’re not capturing that in the by-right development of the Rural community.

What do you think real estate taxes are for, genius?

The whole intent of the UDA was to capture the development. That’s where we can better provide services to the community. So, again, the emphasis is “Get the growth.” I mean, there’s a reasonable balance, but “Get as much growth as you can into the UDA where it’s more cost-effective for the County.”

We still have to provide the services, build the schools, but it is still a heckuva lot cheaper if we do it in the UDA then spread it throughout the County.

Prove it.

So we said, “Possible solution? The TDR program.” You’ve heard a lot about it–I don’t know if people did readings before they came in–but everybody– I was looking online the other day and there’s over a hundred TDR programs in existence throughout the country. And everybody has their pros and cons and their own experiences, so I’m going to tell you a little bit about what we encountered reflective of what the state environment is–the state code, the lack of impact fees. And to some degree the lack of impact fees is actually beneficial to a TDR program the way we’ve set it up.

And there’s your solution. (I’m just going to flip through those real fast.) The developer, obviously, if he goes and purchased TDRs, he could avoid the lengthy rezoning process. He could avoid the expense of doing a TIA, of doing preliminary engineering, of having to address the off-site transportation impacts that he would be creating.

And obviously there’s no proffers. So he doesn’t have to worry about the cash proffer which is generally accepted to mitigate the impacts.

Most important here is what I underlined. The non-stop mindset of our Board of Supervisors was “Those houses in the Rural Areas are not contributing to offset the new development impacts that they’ve created.”

That’s because your Development Impact Model is flawed. It does not take into consideration the amount of taxes paid by the property owner to the County and the State such as real estate taxes, personal property taxes, gas taxes, income taxes, sales taxes, meals taxes, and so forth.

So right off the bat–in Frederick County we use a Development Impact Model to sort of assess what the impacts are. We can break it down in the capital side of things, we can break it down in the operation side. But on the capital side, our Model suggests that there’s close to a $25,000 impact on schools–this is capital–schools, fire and rescue, recreation, parks.

Oh, poo. The latest DIM puts that number as less than $18,000 and it still doesn’t take into consideration the property taxes regularly paid by the owner. I guarantee you that the average homeowner in the Rural Areas pays more in property taxes than what he consumes in County services.

And then, that doesn’t even look at transportation.

Seriously, how many roads does the County have to build/maintain without the use of VDOT funds?

And the developer typically will–I don’t know what the real number is because everyone does magic, but typically on the development side they’ll argue that there’s a 5 to 10 to 15 thousand dollar additional transportation contribution they make to get their projects approved. So there’s significant values that you gain as a community through the proffer system. And if you’re in the Rural Areas having development, you don’t get any of that money.

Oh boo hoo.

So the County says, “We’d like development in the UDA.”

Cuz that’s where the money’s at.

“Long term it’s the vision we’d like; it’s the type of community we’d like. And it’s also the more cost-effective to operate the County.”

Sounds like someone’s budget has gotten out-of-hand.

So, let’s talk about Frederick County and our TDR program. I don’t know if people know where we are. We’re at the northern-most part of the state. Interstate 81 runs north-south through us. The City of Winchester is in the middle of us. We’re about 50 miles from Dulles Airport, 70 miles from Washington, D.C.

During the boom that everybody saw, we experienced significant growth in the commuting population. Statistically we are our own MSA. We actually have more people commute into Winchester and Frederick County for employment than commute to Northern Virginia. I suspect over time that’s going to change because of our proximity to the Northern Virginia technologies and things like that.

And it’s much more affordable out where we are.

Not if you central planners get your way.

But we’ve got about 75,000 people based on the Weldon Cooper numbers. In the City of Winchester I think there’s about 25,000. So the ballpark is about 100,000 people in this community. About 89% of our county is still identified through comp. planning as Rural Areas. So that says that our UDA covers–actually the UDA covers about 10% of the county. We have a certain–we call it a SWSA–but it’s a sewer service area for industrial only that stretches a little bit out of the UDA. But you can get a sense (the bottom bullet there), approximately 12,000 acres of Rural Areas land has been developed and lost since 2000.

It’s not lost. The land is exactly where it has always been.

Easy way to get there: 2500 building permits. Our density is one house per five acres. But you can see, just generally speaking…

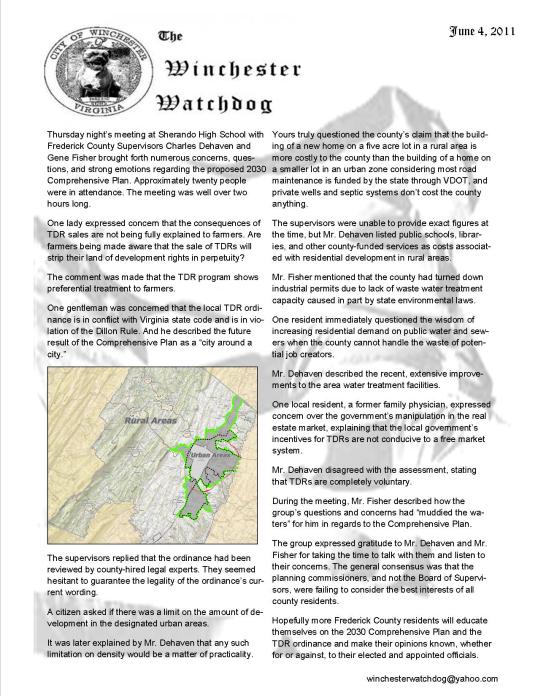

[He points to the screen to show were the UDA is located and where the industrial area has been stretched up the I-81 corridor. “But we don’t allow housing up there,” Mr. Lawrence says. “But most of our residential growth we try to concentrate in that area of the county.” He points to the area beside the City, east of I-81.]

How did we get to TDR? Well, in the summer of 2008, our Board of Supervisors said (and this is part of the planning, everybody who is part of planning–you get this one), “Okay, I want you to hold a public hearing. Downzone the county. Downzone the Rural Areas of the county. We want to go from instead of one house per five acres, I want a one per ten acre.”

So, we held a public hearing to get input. And let’s just say that before we even opened the doors that night, we knew that we were going to have a problem. There’s a couple people in here that used to work with us, and you know that typically when we hold public hearings we don’t get a lot of people showing up. And when we set out for that downzoning, we filled the rooms, we filled the hallways, the people were standing outside the building. So, the Planning Commission fulfilled their expectation–we held the public hearing, and we didn’t even have to report to the Board of Supervisors. They were all standing in the room. They said, “Don’t bring that to us. We don’t want to see that.” [Laughter]

So what the Board did is say, “Okay, we’re seeing more growth in the Rural Areas than what we want. We’re not going to be able to downzone. There’s obviously not support for that.” Three or four weeks after that meeting, the Board established a subcommittee to do a real intense look at the Rural Areas and try to figure out “What can we do?”

The problem was loss of farmland. The problem was houses that were showing up there. Anybody you talked to said they didn’t like that as a community. How do we get a compromise, how do we find a point to get there?

Um, do we live in America, the land of the free, or not?

So we met for the better part of four months, every other week. We had three Board members, three Planning Commission members, I had folks from my staff, just putting all of our energy into it. We went in through everything–there was a mention about the Toolbox, the VAPA Virginia Planning Toolbox–we went through everything that we could find that’s allowed in Virginia to help manage our growth. And the UDA, obviously, we’re already doing it. And what we found is we hadn’t touched TDRs. So we started talking about the TDRs.

Part of the subcommittee we had developers participate, we had the rural farm bureau, and we had the rural land owners participate. And everyone said, “I think TDRs are where you need to go.” And so we started concentrating on that.

Ultimately we adopted a policy to the Comp Plan for the Rural Areas which included a couple of things we needed to do: health systems was one, but TDRs was the most important through the discussion. And then ultimately we created the TDR ordinance, and it was adopted a couple of months ago.

This is telling. Remember in an earlier post where I mentioned the tighter restrictions on private wells and septic systems? According to Mr. Lawrence, the Board of Supervisors set up the Rural Areas subcommittee to figure out how to impede growth in the Rural Areas. It appears that one way the subcommittee came up with to impede residential development in the area was to make private well and septic systems more expensive and complicated.

Our TDR ordinance says– Okay, in everyone’s ordinance and comp plans you always have to have your purposes and goals, and we were trying to identify them. And we said, “Providing an effective and predictable incentive process for property owners of Rural Areas and agricultural land to preserve their land. Help direct the residential growth to the UDA.” And then “How do we do it most efficiently and effectively? How do we do it so it’s not going to be cost-burdensome on the property owner, on the farming community. How it’s going to look attractive to developers.” So we had some–I guess what I call a common sense approach–but we made sure that everybody knew why we were doing this. “Let’s make it cost-effective. Let’s make it so people want to participate.”

The way we broke it down is we looked at our county. We have an Urban Development Area. We only provide water and sewer service in the Urban Development Area. We have flexible zoning for the Urban Development Area, being that there is one residential zoning district which has performance standards. So, in our UDA if you get your residential performance zoning, you can do single-family houses, townhouses, apartments. We let the property owner figure out what works for his site.

How about you do that THROUGHOUT THE COUNTY since this is AMERICA? Sorry, I’m annoyed.

So we said, “Okay, now let’s look at the Rural Areas. Let’s look at the Sending Areas–well, the areas that we want to protect.”

You mean, what your cronies want to protect and avoid paying taxes on, not what the entire county wants to protect.

We weren’t interested in being selective. It was pretty clear from the elected officials that we don’t want to look to certain regions in the Rural Areas and say, “well that’s a better piece of property to preserve.”

Bullcrap. Isn’t that why you have Limestone areas as a 1:1.5 ratio and Sandstone/Shale areas as a 1:1 ratio?

So what the Board said is, “I want you to look at everything outside the UDA and let that be your Sending Area.” And we whittled it down a little bit. We said, “Okay, it’s got to be RA zoned, Rural Areas zoned. It’s got to be outside of the UDA. Also, outside of our sewer and water service area because sewer and water service area is directed for industrial/commercial opportunities. Obviously you’ve got to show it on your map because that’s the Comp Plan requirement.” And the last two bullets are extremely important. We said, “It’s got to be twenty acres or greater in size” because we didn’t want to nickel-and-dime it. We didn’t want somebody coming in and selling one lot here, one lot there. And when we started looking at the type of subdivisions we were getting in the Rural Areas, there was typically starting at twenty acres. In Frederick County, twenty acres could be cut essentially into a total of four lots. And the last bullet is most important. We said, “Okay, you can’t sell your development rights unless you have an ordinance by-right to actually subdivide your property.” In Frederick County you have to have state road frontage before you can even talk about a subdivision. So that became an important element because we didn’t want to give somebody who has a hundred acres with no access–he can’t do a subdivision, so why give him development rights? We’re not preserving anything. The nature that he can’t do a subdivision because he has no road access inherently already protected that land from growth.

Wow. Landowners with no road access–you’re screwed. Your land has no value. Thank your local government.

We also said, “You gotta keep some densities on the Sending properties.” And this came out of the Board Chair. He said, “Hey, if somebody’s not thinking and they sell all their development rights but the one, what happens with this 300-acre parcel? That means you’re going to have a 300-acre parcel forever.

I bet the conservationists want to bonk the Board Chair over the head for that one.

So the suggestion was, okay, you keep a dwelling right for every house on your property, and for every hundred acres you have to keep a dwelling right. So that forces the property owner today to keep some development opportunities

–albeit not much–

for whether it be for himself or future landowners.

We don’t count anything as far as creating your development right numbers, if your property has easements in it–you don’t get credit for that. If you have floodplain–environmental features–you can’t develop the floodplain, the side of a mountain, wetlands, so we’re not giving you credit for that either as far as selling development rights. And obviously you have to be in good standing with the County before we talk to you. Pay your taxes.

You had better hope the government never designates your land as a “wetland.” Not only could you not develop your property, they won’t give you any imaginary development rights to sell either.

We did find that there was a necessary multiplier. We needed to do bonus densities. We found that we wanted–we needed to do it because we needed an incentive from both the developers and the farmers. Obviously the developer who wants to go out and put a subdivision together–it’s a lot easier if you can go to one property and buy a bunch of rights than have to go to ten different properties to get the total number of development rights that he’s looking for. So we created a three-tiered density bonus. And I’ll show you a map in a minute. You’ll see how we broke it down.

Sending Area #1, which we said, “You can sell two development rights for every one development right on your property.” Does that make sense? 2 to 1? We said, “It’s going to be our Agricultural and Forestral District.” In our community we have a heavy orchard industry, so a lot of our Ag District is orchards. If you drive through the countryside you can actually, without even look at this map, pretty much guess where the Ag Districts are simply because it’s heavy orchard area.

So we said, “Okay, if you’re in an Ag District we want to give you an incentive to sell your rights. We want to keep you in agriculture.”

Why, oh, why is the government meddling in private markets? Didn’t they learn their lesson during the housing boom-and-bust?

We said Sending Area #2 is a strip that runs west of Interstate 81 and east of Great North Mountain. It’s the best soil we have in the county.

Except for your dishwashers when they collect all that limestone.

I’m not going to say all the orchards are there

–because we know they are not–

but a majority of the orchards are running through that area. And unfortunately, it’s the best soil in the county for agriculture, it’s also great soil to get a drainage field on too. So that became one of the challenges. So we said, “Let’s create an incentive for those people to help keep their farm.”

And then, as I noted earlier, the Board didn’t want to exclude anyone from the Rural Areas from the program, so they said, “Everybody else, if you’re in the Rural Areas you can participate in selling your development rights.”

So you can see just on the map, the dark brown is the Area #3 which has a 1 for 1 exchange, the gold is a 1 to 1.5. And then the green is your Ag District which we hope is going to be the one we’re able to save most.

We took it one step further. We said, “Let’s use GIS.” Obviously the way our program is set up, when somebody comes in to see how many development rights they have, we’re going to run through the specifics on their property to come up with a number. What we felt was we ought to use GIS to get a sense. We have a lot of the area identified as Sending Area, but when you run the road frontage requirements, the twenty acre requirements…There is still a lot, but you notice it’s not nearly as much as we had before.

So the red is the areas that could qualify for–and that’s a cursory view, that’s using GIS which ties in tax map data. When you get site specific you might find things you weren’t aware of, but there’s a general snapshot.

The Receiving Areas: well, it’s pretty easy. We wanted it to be within the Urban Development Area. We wanted it to be within what we call our Rural Community Centers. We have a number of Rural Community Centers throughout the county that are just–Susan, in the audience, she helped us with some of these things–they’re just like crossroads that have been there forever. They’ve got a sense of community. Don’t have anything zoning specific for it. But we said, “We’re going to set up the TDR ordinance so that those Rural Community Centers, as we develop ordinances that would work in the land use plans, they could be Receiving Areas.”

More laws. Yay.

And most important, the Receiving Areas had to have public water and sewer and state roads.

So the Receiving Areas became the Urban Development Area which is around the City of Winchester, and then you can see out west, I guess that’s the Gainsboro Rural Community Center. [Shows various maps.] (Same map, just a little more clarification.)

Okay, let’s look at our UDA–our potential Receiving Areas. You probably can’t tell but the UDA has all the pink and the white. Well, when you zoom in, those are the properties that would qualify for accepting TDRs. [Screen shows map of red-colored Potential Receiving Properties.] We’ll get some statistics in a little bit.

From a process perspective, the ordinance sets out how you come through the process. It says, “If you’re the farmer (I’m going to say ‘farmer’ but it’s really landowner), you can submit an application to us. We’ll analyze your property. We’ll tell you how many development rights you have to sell.” That’s the letter of intent. We have a certificate; which once you’re ready to sell it, we’ll issue a certificate which is the letter that you can then go out and market and transfer that ownership of these development rights.

There was talk earlier about legal rights. A fee simple and that sort of thing. Obviously you can’t sell a development right–just like you can’t sell your property unless you have everything cleared–you can’t sell a development right unless it’s gone through and had the title searched and shows that you have the right to sell that development right. I think one of the hurdles that we may come into is obviously a lot of properties have mortgage and liens on them, and that’s going to cause some conflict when you try to sell your development right because you’ve got to clear the lien. You’ve got to have the lien holder authorize you before you can sell that development right.

And just some of the information–this is all in the code that was handed out–but some information that we have as we start tracking TDR letters of intent and sales. What we’re doing in Frederick County is when you transfer that right, when the farmer sells it, we do banking so that the developer can buy it and apply it instantly, or he can bank it and just hold on to a bunch of rights. But as soon as it transfers from that farmer, we require a restrictive deed covenant to go on the property.

There was a lot of discussion whether you say “okay, once these development rights are removed do you do easements, conservation easements? Do you do covenants?” Our elected officials felt that the deed covenant was the appropriate route to go. A lot of it because if you do a conservation easement, who is going to monitor it? If it’s a deed covenant, it becomes a three-way agreement that the County is now a party to. And through the method [?] of the GIS, we can track the property so obviously if we’re doing our jobs and our due diligence when we review subdivisions, we’ll know whether or not there’s any development rights on a property before we do the subdivision. So making us party to the deed covenant helped us enforce it through that method. Normally we don’t enforce covenants; it’s a private matter. But since we’re a third party to it, we can start enforcing it.

Yay! for Big Government!

The Density Bonus, which we found is extremely important, and what we said is, “Okay, when you apply TDRs, you can apply them in the RA zoning within the UDA.” So basically on a property in our Urban Development Area that hasn’t gone through rezoning process, you could buy development rights and essentially develop that property to its fullest extent as a residential subdivision, as an RP zone.

But you could also buy development rights to enhance your residential zoning. And we established caps based on your acreage size–we let you do a 50% bonus on your maximum density. So the table which you have in your package is straight out of the ordinance. It sort of sets that framework.

You’ve got to track–when someone sells that development right, it’s extinguished. Then you track who holds it and then where it’s going to be applied ultimately. We’re going to do that through the GIS. We haven’t exercised a transfer yet, but we’ve set up the GIS so we’ll be able to track all the different exercises.

We put together this little bullet slide–5 steps–to simplify the ordinance for anybody that wants to participate in it. All this stuff is available on our webpage. We want the public to be aware of what’s going on. The first step is your sending property criteria which talks about the process for the TDR application. And I will say that to go through the whole TDR transfer process, we felt it was necessary to do minimal fees. So there’s a lot of different steps where you have to come by department to get authorization, but the total cost is just about $1000.

Of course, the County has to have its fingers in that pot, too.

So the idea is we didn’t want to make it fee cumbersome; we wanted to make it simple for the farming community to come in and make application and get that process going.

One of the challenges we heard is the farming community didn’t want to subdivide their property. They wanted to sell it outright because if they tried to subdivide it, they’d have to front the costs for the drainfield search and all the engineering. They don’t have the money, was the argument. So we said, “Okay, when we do a TDR we’re going to minimize expense to you.”

Wouldn’t it be nice if they did that with the building permit process?

“We want it to be attractive; we want it to be less burdensome.” So we just outlined the various steps as to how you go through the process (and we touched on some of this already.)

The neat thing is when you apply the Receiving Areas–once you purchase your TDR rights in the Receiving Area–you actually just go through a normal subdivision process. It’s not a legislative rezoning but it’s an administrative process where you do what we call “Master Plan.” You do your subdivision design plan. And on your subdivision design plan–in your plats–you just certify where you’re getting those TDR rights from. So there becomes a record of why you’re allowed to do that subdivision.

The application process is pretty simple. What it basically says is “Do you have any liens on your property? How many acres do you have? How long have you owned it? Who is the owner of it?” And we let you tell us. “Do you have any water features that we need to be aware of? Have you done any subdivisions on the property?” We want the property owner to just tell us what they’re aware of so when we do our check, it’s sort of a checks-and-balances so we’re not missing anything from their description for their Sending Area property.

And some of the statistics…When you look at our Sending Area, (I’m going to round up numbers), you’ve got about 100,000 acres in the Sending Area total. And then when you’ve broken it down just using GIS queries. So you can see that there’s approximately 25,000 dwellings that could be transferred. Now I will say that’s before we actually did the properties that actually qualify, so the number is going to be a little bit lower. But you have 25,000 dwellings that could be developed in the Rural Areas of the county as a by-right exercise.

But when you look at the UDA, which is where we want to receive things, we have the potential to receive–we have 5,000 acres under what’s available–but if we receive all those transfer rights, you would actually take the UDA density from what we plan as a 5.5, and if you add the TDR rights you put it at about a 10.8 units per acre. Now I think that’s important to point out because the new UDA state code talks about the targets for our population size community is about 4 to 12 units per acre.

So this insidious crap is coming from the State (who ultimately gets it from the Feds, who gets it from…?)

I will be honest, with our TDR program we didn’t know where we were going to end up until we started doing the numbers, but we felt like “okay, we’re in the target area” so that’s a comfort level with us locally and it also continues to achieve what the UDA state code talks about.

We ran a couple of scenarios. Now these are real properties but I’m not going to tell you where they are. But a three hundred acre farm–it’s got a dwelling on it–it’s in our Sending Area #3, so it’s a one per one transfer. It’s got about 58 acres of environmental features, easements.

Any time you hear the word “environmental,” know that it involves the government taking away property rights.

So when you do the math you have about 54 units that could be transferred. Well, because of the size of the land, because he has a dwelling, he could actually transfer 51 units. So there you go. He can get a certificate that says “I have 51 units I can sell through TDR.”

And then we looked at a couple of examples within our UDA. (I’m sorry, that’s the 300-acre farm. You can see it’s got some floodplain on the west. It’s got some wetlands on the east. You’ve got some little steep slopes in the middle. But you can see it’s a nice piece of land.)

Well, we picked three scenarios where those TDRs could be received and it’s infill development. You’ve got a two-and-a-half acre site. It’s on one of our main road corridors. It’s in the middle of our UDA. It’s targeted for residential growth. Well, it’s RA zoned presently, so that says it has the ability to do one house in its current zoning. But if you transfer those development rights, if you transfer the 51 development rights that we talked about, he could capture all this. But he could also buy 27 development rights.

The end of the story is, he could do 4,000 square foot lots on that property and not have to go through the rezoning. Not have to pay the engineering costs, the transportation impact fee analysis, or any of the proffers. He just has to buy the development rights.

Similar situation, this property is a little bit larger. It’s ten acres in size. Today it is actually zoned for residential development. So that says its underlying zoning gives 5.5 units per acre as a by-right. With TDRs, he could put up to 82 units on the property if he buys TDR rights because he can take 5.5 units, increase that by 50%, so he could actually have a total of 8 units per acre on this property. So he could buy 26 density rights from a farmer. So that 300-acre farm can now be preserved. And basically this comes out to be about 4 – 5,000 square foot lots also.

I don’t know about everybody else’s community, but traditionally we were seeing quarter acre lots–10, 12, 15,000 square foot lots in the Urban Area. They’ve gotten a lot smaller. Actually through our ordinance we’ve allowed for lots as small as 3,750 square feet.

Ha! “We’ve allowed…” Amazing.

We call them “single family small lots.” They’ve got to put a community center or something in once they’ve got to a certain size. But that type of infill is what we think is necessary to achieve UDA standards of the state, but also it’s a better use of land. Minimize the sprawl, pack people in.

Well, there it is.

And I think we’ll see more of that as time goes on.

For the last couple years, I’ll say since 2006, 2007 we’ve seen a lot of the smaller lots come through. And the national builders were coming to Frederick County and they were pursuing a little more flexibility. And they were starting to develop some of these smaller lots. So I think TDR has an opportunity just on what we’ve seen recently.

The third scenario we have is 25 acres. It’s next to town houses. You could actually continue that townhouse development and your density would be relatively consistent with what we already have out there. So, again, you’re saving a 300-acre farm, the developer is getting to continue his townhouses or whatever he wants to do. He doesn’t have to go through the process–it’s a cost-savings for the developer if he buys those TDR rights.

So, the local government makes residential development expensive and time-consuming, and then creates an artificial market to sell artificial “rights” with the promise that residential development will be cheaper and quicker.

One thing that we are working on is we currently don’t have I guess the more traditional TND District. We drafted the ordinance last year, and the TDR program superceded it, so we had to shelve it, and we’re going to dust it off and start up again in the near future. But we set the TDR ordinance up so we adopt the TND, which is going to allow for the residential structures on top of the commercial centers and things like that, you can do transfers into the TND. And obviously, as I noted earlier, we need to create the zoning district for the Rural Community Centers. We’ve already set TDRs up so that they could transfer there. But the Rural Community Centers need to have a zoning that would apply to obviously allow lot sizes consistent with what you see in our community centers which are typically, I’ll say, half acre lots, a little bit smaller sometimes. But right now it’s a one house per five acre density, so we have to clean up the community center zoning.

The conclusion–and this is my conclusion, this is Frederick County’s conclusion–but we think TDRs are a good tool to preserve the agricultural and forestal land, and also to redirect the growth to the UDA. Obviously the success or failure is based on the marketplace. What we think we’ve done is set up a program that can be attractive to both the farming community and the development community. Minimal government involved.

HAHAHAHAHAHA!

Our involvement is basically just tracking it, watching it go through the process, making sure checks-and-balances are being met. But it’s not a legislative approval process. And time will tell.

I’ll note that, I got an email from my office that in today’s paper up in Winchester they had a big article on TDRs. So it’s something that, you know, you need to educate the public. And we went through two years of talking about preserving the Rural Areas, talking about TDRs, and it’s still showing up in the newspapers. So we’re fortunate that our local media still has an interest in it, but also we want to keep talking about it, we want to keep promoting it–talk to our developers and farm bureau and all that and let them be aware of what’s going on. If they like it but there’s a problem, we have good enough communications they’ll let us know where the shortcoming is and we can assess whether it needs to be fixed.

And there’s some resources–the presentations that you’ve seen on TDRs today, they’re all on our webpage. We put a package together because we’re constantly talking to people. All of our applications and stuff are online also.

And I’ve got to comment on two things: Ted McCormack is here, and Ted is the TDR expert in the state. So he’s done presentations on the education and state code aspect. And a lot of the information that you saw in the first presentation is his, so I’ve got to give him credit for that. And then Candice Perkins with my staff, she is the one that spearheaded the actual drafting of the TDR ordinance. She was hoping to come down today but she has a newborn and wasn’t able to travel. But I want to give her credit because she has put a lot of effort and energy into it.

That’s my presentation and I’m certainly available to answer any questions.